America's History of Protectionism

Protectionism has been a frequent feature of the republic since its founding.

IN LATE August 1985, while President Ronald Reagan vacationed at his ranch above Santa Barbara, California, his political director, Ed Rollins, had dinner one Saturday night with reporters for the New York Times and Washington Post. The mischievous politico leaked a story that received front-page treatment Monday morning. President Reagan had decided, the newspapers reported, to reject the pleas of U.S. shoe manufacturers for import tariffs designed to protect them from foreign competition. No big surprise there. Reagan was known as a fervent free trader, hostile to tariffs and other barriers to global commerce.

But discerning Washington hands detected a curious disparity in how the two influential newspapers handled the story. The Post focused on the shoe decision, noting only in passing, that Reagan also was weighing actions to counter unfair practices used by U.S. trade partners. The Post headline read, “Reagan Set to Reject Shoe Curbs.” But the Times turned that around with a top headline that stated, “Reagan Weighing Trade Sanctions, Officials Report.” The paper’s lead paragraph emphasized the president’s decision to weigh “punitive actions” against errant nations abusing America’s free-trade principles.

This led to confusion about Reagan’s true stance on trade at a time when that issue was roiling the country’s politics and when some White House clarity was needed. The president had his press secretary inform White House reporters that Reagan would deliver a major trade address in about a month. A trade-policy struggle within the administration ensued that was so intense that the president’s speechwriters were barred from creating the final draft of the speech.

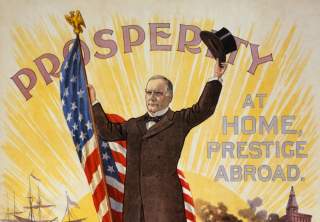

This episode exemplifies the contention that has surrounded the trade issue throughout American history, starting with Alexander Hamilton, the country’s first treasury secretary and also its first significant protectionist. Today, protectionism is back. The main drivers of this new surge are Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump and the Democratic insurgent Bernie Sanders. Even Hillary Clinton is playing a role. Far from being an aberration, opposition to free trade has been a constituent part of America’s history.

THE ED ROLLINS episode reflected the fact that Reagan faced a political problem of serious magnitude in his second term. Protectionist sentiment was growing in Congress, unleashed by burgeoning imports primarily from Asia. Some three hundred protectionist bills had been introduced in Congress to help various industries beset by foreign competition, including electronics, appliances, textiles, clothing, toys and automobiles. The struggling shoe industry had placed itself at the vanguard of this movement. In fifteen years, U.S. shoe manufacturers had shuttered two-thirds of their domestic factories as shoe imports to the United States grew from just 22 to 76 percent. In 1977, Reagan’s predecessor, Democrat Jimmy Carter, had imposed quotas on shoes imported from Korea and Taiwan, but Reagan had allowed them to lapse.

Now, in the autumn of 1985, some Reagan aides, notably Rollins himself and U.S. Trade Representative Clayton Yeutter, were telling the president that, if he didn’t throw a bone here and there to beleaguered manufacturers, angry protectionists in Congress would gain sufficient strength to challenge the administration’s free-trade stance. Officials at the Commerce, Labor and Agriculture Departments agreed. But Secretary of State George P. Shultz and Treasury Secretary James A. Baker III opposed imposing protectionist measures unilaterally. They favored negotiations with trading partners to end unfair trading practices, using existing sanctions authority as a bargaining chip.

The shoe industry presented a revealing case study. The U.S. International Trade Commission, an independent federal agency, had responded to industry pleas by recommending quotas on shoe imports, restricting them to 60 percent of the American market for five years. But footwear retailers retorted that restrictions would cost consumers billions of dollars in higher shoe prices. One dissenting trade commissioner said the quotas would only save twenty-six thousand U.S. jobs at the cost of $1.28 billion to consumers annually, three times the wages of the workers whose jobs would be saved. Reagan rejected the quota idea. Other administration officials suggested a 30 percent tariff to be phased out over five years—a compromise designed to give the domestic industry relief without imposing actual import restrictions. Reagan rejected this option as well. One official told reporters that he “just didn’t buy the argument that we should accept a small dose of protectionism to head off a larger injection.”

But the administration still needed a coherent policy. Reagan needed to assuage agitated congressional protectionists while still preserving his fundamental free-trade convictions. The presidential speech, slated for Monday, September 23, 1985, was designed to serve this purpose. Just after noon on the Thursday before the scheduled address, White House speechwriter Bentley Elliott completed the final draft. Elliott and his fellow speechwriters saw themselves as the president’s keepers of the conservative flame—free-market believers who followed the dictum so popular among administration hard-liners, “Let Reagan be Reagan.” The draft was a rousing defense of free trade and a pugnacious attack on the nettlesome protectionist forces swirling around Capitol Hill. This, thought Elliott, was what Reagan wanted.

But when the draft reached the office of White House Chief of Staff Donald Regan, he exploded. One of Regan’s top aides called it “an abomination,” and Regan thought the draft took on a politically risky tone that could anger members of Congress and fuel protectionist fires. Regan sent it back for a rewrite, then called Elliott into the Old Executive Office Building to say the task was being yanked away from him. A Regan aide, Alfred Kingon, would write the speech in the West Wing. Out went the rousing free-trade rhetoric; in came rough language directed at what the United States considered unfair practices employed by its trading partners. A top Regan hand dismissed the speech-writing team as “just a bunch of ideologues who are hep on free trade.”

When a Wall Street Journal reporter got his hands on Elliott’s final draft and utilized it to pry out elements of the internal dispute, both sides used the reporter to cast darts at the opposition through quotations in the subsequent story. Thus did a nasty internal controversy become a public spectacle. And all this occurred in an administration that fully favored free trade; the only question was the tactical response to protectionist agitations welling up from within the country. Such was the capacity of the trade issue to wreak political havoc.

PROTECTIONISM HAS been a significant part of the country’s trade history going back to its first revenue law, crafted in 1789 by George Washington’s financial wizard, Hamilton. This original tariff bill imposed an average taxation level of only about 8.5 percent on imported goods. Hamilton argued that any protection encompassed in those duties, as opposed to revenue requirements, should be discontinued as soon as protected industries established themselves in the American economy. But northeastern industrialists predictably asserted that protection should be substantial and permanent to ensure national prosperity.

The trade issue comes into focus through an understanding of the political conflict between Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson at the dawn of the American republic. Hamilton favored executive power wielded by elites for the purpose of economic expansion and national greatness. He advocated federal-level projects and policies—particularly a powerful national bank and protective tariffs to help budding manufacturers and finance federal action—to pull up the nation from above. Hamilton’s views, refined by the next generation of political leaders, became the foundation for Henry Clay’s Whig Party and his philosophy of government, which he called the “American System.” This model emphasized the construction of federal public works such as roads, bridges and canals. High tariffs would also be enacted, in order to pay for civic programs and boost industrial expansion.

By contrast, Jefferson and his later devotee, Andrew Jackson, opposed high levels of governmental intrusiveness into the private economy. Such policies, they argued, would inevitably lead to special privileges for the favored few. They wanted to keep tax levels as low as possible and reduce federal interference so the people could build up the nation from below.

The Hamilton-Clay forces won the first battles. They created a national bank (actually, two banks, both chartered at different times by the federal government) and enacted a major tariff bill during the presidency of John Quincy Adams, whose philosophy was in the Hamilton-Clay mold (Clay was his secretary of state). This bill slapped high duties on iron, molasses, distilled spirits, flax and various finished goods. Northern producers thrived under the protections of the tariff. But southerners hated the bill for two reasons: it raised prices on necessities not produced in the South; and by crimping the importation of British goods, it reduced Britain’s ability to purchase southern cotton. Southerners called Adams’s import tax the “Tariff of Abominations.”

South Carolina decided it would escape this particular abomination through a highly provocative doctrine called “nullification.” The idea was that the state would exercise what it considered its sovereignty in declaring the law null and void. Here we had the country’s first really high tariffs generating severe regional tensions that culminated, during the subsequent Jackson administration, in an ominous constitutional crisis. As a Democrat, Jackson despised high tariffs, but he had declined to expend the political capital required to reduce the Tariff of Abominations. He found himself in the position of having to defend the tariff against what he deemed treasonous threats from a southern state. Jackson quickly made clear he would not tolerate this assault on the Constitution.