How to Wage Political Warfare

Both Russia and China are governed by opaque, highly centralized and increasingly personalized governments that are well suited to the darker arts of statecraft. Political warfare, for such regimes, is second nature.

POLITICAL WARFARE is back, and the United States is losing. As great-power competition has intensified in recent years, China and Russia have undertaken multi-pronged offensives to undermine American influence and erode the U.S.-led international order. These offensives have included defense buildups, geoeconomic initiatives, paramilitary coercion and even (in Russia’s case) outright military aggression. They have also featured determined political warfare campaigns.

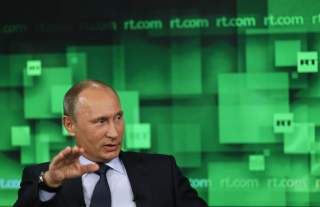

Political warfare is the use of non-military means to manipulate and undermine the political system of a competitor. Political warfare with Russian and Chinese characteristics involves the use of myriad tactics—cyberattacks, disinformation, electoral meddling and others—to disrupt and destabilize the political systems of America and its allies, thereby rendering these countries less geopolitically effective. Authoritarian powers are “using information tools in an attempt to undermine the legitimacy of democracies,” warns the 2017 National Security Strategy, to “shake our shared commitment to our values, undermine our system of government, [and] divide our Nation.” As the turmoil sowed by Vladimir Putin’s intervention in the U.S. presidential election of 2016 shows, these campaigns are having an impact.

It is unsurprising, then, that the U.S. national security community has so far focused mostly on diagnosing the problem of authoritarian political warfare and considering how to defend the country from these attacks. Yet if defensive measures are indispensable, they are also insufficient. For the United States to hold its own in today’s great power competitions, it must think and act offensively in the realm of political warfare: it must do to its rivals what they are seeking to do to it. Taking the offensive is vital to exploiting the principal vulnerability of those rivals—their corrupt, illegitimate, authoritarian political systems—and ensuring that America is not unilaterally disarming in a critical area of competition. And although Washington has lately fallen out of the habit of waging political warfare, that practice is hardly alien to its diplomatic tradition. America has decades of experience employing political warfare against an authoritarian challenger, experience that can inform a renewed offensive today.

IF WAR is politics by other means, then authoritarian political warfare is war by other means. Neither China nor Russia have so far been willing to take on the United States and its allies militarily. For years, however, they have been pursuing revisionist geopolitical ends in part by seeking to weaken and distort rival political systems. These campaigns seek to stifle criticism, soften up competitors and impair the performance and prestige of democratic systems. The overarching goal is to render the global environment more conducive to the maintenance of authoritarian rule at home and the expansion of Russian and Chinese power abroad.

As with so much of what Russia and China do today, this behavior is rooted in burning ambition and intense insecurity. On the one hand, Russian and Chinese leaders desire to expand their countries’ influence, reclaim lost prominence and power on the global stage, and weaken the rivals that stand athwart these designs. On the other hand, both the Russian and Chinese regimes see themselves in a perpetual struggle against the West for strategic independence and survival. Chinese and Russian leaders view Western liberalism as an ideological contaminant that threatens their power and the cohesion of their societies; they believe that America and its democratic allies are determined not simply to frustrate their geopolitical ambitions but, ultimately, to overthrow their regimes.

Given the perceived stakes, Russia and China have adopted comprehensive approaches to competition with the West, with political warfare at the center. After all, political subversion and conflict were essential to the rise and survival of communist regimes in both countries during the twentieth century; these experiences are etched deeply into contemporary Russian and Chinese institutional memories and loom large for contemporary leaders who emerged from those traditions. Moreover, both Russia and China are governed by opaque, highly centralized and increasingly personalized governments that are well suited to the darker arts of statecraft. Political warfare, for such regimes, is second nature.

The resulting campaigns have been expansive and multi-faceted. They have included measures designed to interfere in elections, corrupt legislative and policymaking processes, breed economic and financial dependencies, cultivate ties of “friendship” with political and business elites, co-opt diaspora communities and other influential groups, spread disinformation among the public, extend state-sponsored influence through ostensibly private entities and civic organizations, influence the agendas of universities and think tanks, and expand the reach of state-directed media within foreign countries. Russia’s election meddling and sowing of “fake news,” China’s sponsorship of Confucius Institutes at universities across the United States, and Beijing’s efforts to restrict anti-China criticism in America, Europe and elsewhere are recent examples of political warfare in action. Such measures have been deployed not just against the United States, but also against democratic allies—from the United Kingdom and Germany to South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

So far, these campaigns are delivering significant returns on modest investments. While Moscow’s interference in the 2016 presidential campaign may have partially backfired by hardening anti-Russia sentiment in Washington, it also inflamed America’s domestic tensions and political polarization. The effects of Chinese political warfare have been subtler, but no less damaging. Recent revelations show how Beijing’s sophisticated operations have led Western universities, think tanks, media outlets, private companies and even politicians to openly support Chinese policies, acquiesce quietly to Beijing’s positions and engage in self-censorship on topics that China deems sensitive. Indeed, it is a measure of the effectiveness of Chinese political warfare that America and its allies have been relatively slow to face up to the massive geopolitical challenge Beijing presents.

THE THREAT that authoritarian political warfare poses is therefore real and persistent, and strengthening U.S. defenses is imperative. Hardening electoral systems and cyber defenses, shining greater light on Russian and Chinese influence activities, cracking down on the dissemination of disinformation, devoting additional intelligence resources to detecting malign activities, and strengthening cooperation with allies and partners facing similar challenges are critical to limiting the damage authoritarian political warfare causes. For several reasons, however, a purely defensive posture is neither sufficient nor desirable.

First, political warfare is an arena in which the defense faces inherent disadvantages. It is generally less difficult and costly to conduct cyberattacks than to properly attribute and defend against them; it can also be cheaper and easier for a sophisticated adversary to spread disinformation than it is to detect and correct it. Political warfare is similar, in this way, to the missile to anti-missile competition—the cost-exchange ratio favors the offense. As does the innovation curve: any strategy that relies solely on defense will put America in the position of responding, probably belatedly, to evolving Chinese and Russian techniques.

Second, a static defense is particularly problematic for a liberal democracy. Because the American system is so open, it offers countless entry points and avenues of influence for nefarious actors. And because government power is limited, divided and decentralized, it is particularly difficult to cover the resulting vulnerabilities. As Barack Obama acknowledged in 2016, “open societies” face “special challenges” in fending off political manipulation.

Yet the asymmetries between liberal and illiberal systems are far from wholly disadvantageous to the United States. A third reason for going on the offensive is that America’s competitors are themselves incredibly vulnerable to political warfare. The Russian and Chinese regimes look strong, especially as leaders of both countries consolidate power, tighten political controls and construct elaborate cults of personality. Yet the strength of these regimes conceals a deeper, more fundamental weakness.

Both the Russian and Chinese regimes are flagrantly corrupt, deeply repressive and characterized by extreme concentrations of wealth and power. Their legitimacy is perpetually precarious because it stems from economic performance or the deliberate stoking of nationalism, rather than the inherent attractiveness of the political model. Both countries, additionally, have seen rising popular dissatisfaction in recent years, whether pro-democracy protests in Russia, the large and presumably growing number of “mass social incidents” in China or the seething unrest and brutal repression in Tibet and Xinjiang. Indeed, the reason both countries have well-developed and well-funded internal security apparatuses—the reason both countries are moving deeper into authoritarianism—is that their leaders live in perpetual fear of the population turning against them. Both systems are highly susceptible to political warfare campaigns that would impose greater costs on authoritarian regimes and heighten the difficulties under which they operate.

Finally, a comprehensive approach to political warfare is integral to a comprehensive strategy for competition. The United States need not match China and Russia on every geographical front or in every functional area. But it should address a glaring disparity: the fact that America’s rivals have taken a far more holistic and expansive approach to competition. Russian and Chinese strategies for reshaping the international system employ all aspects of national power to weaken adversaries and influence countries across the Asia-Pacific, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and beyond. Washington, meanwhile, has been slow to recognize such challenges, let alone devise responses that reach across the elements of statecraft. By acting more energetically in the realm of political warfare, America can fill this gap and ensure that it is not simply abstaining from a crucial area of competition. It can also exploit the fact that the United States actually knows this area of competition well.