What is Wagner’s “Value Proposition” in Africa?

Even without the Wagner boss, the Kremlin will want to see the network survive and continue to exploit opportunities as they arise in Africa.

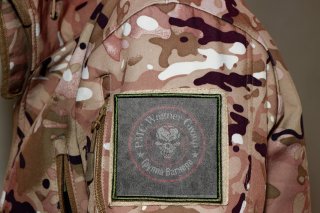

The quiet burial in St. Petersburg this week of Yevgeny Prigozhin may have laid to rest the mortal remains of the notorious mercenary chief, but the Wagner Group which he founded is still very much alive—at least outside Russia. Until the United States and its allies, including partners among African regional organizations and governments, can provide a credible alternative to what Wagner offers, the outfit will not only survive in one form or another but will continue to wreak havoc through wide swathes of Africa and elsewhere. This is because, reprehensible as it might be, there is a strong demand for what Prigozhin’s network offers.

While much of the focus in the aftermath of the spectacular crash northwest of Moscow of the private jet that killed Prigozhin, two of his top lieutenants, and seven other people on the two-month anniversary of the mercenary band’s abortive mutiny and march on the Russian capital was on either how the Embraer Legacy 600 was brought down and who may have been behind an incident that no one believed was an accident, not much attention was paid to where the Wagner boss was immediately before his untimely demise. In fact, as the Wall Street Journal’s world enterprise team first reported, the Russian street thug-turned-mercenary leader spent what ultimately proved to be his final days visiting outposts in Africa where he had not deployed some 5,000 hardened fighters, but also built a sprawling business empire dealing in everything from natural resources to liquor, much of it illicitly. According to the Journal’s reporting, Prigozhin made stops in the Central African Republic (CAR) and Mali and, while in the former country, also met with commanders of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) from Sudan.

In fact, from the information I received from senior African political and security officials—coincidentally, I was traveling in the Sahel at the same time and discussed the Wagner Group’s activities in neighboring countries with them, even before we knew of Prigozhin’s death—not only was he trying to prevent a Kremlin takeover of his African network, but he was actively trying to expand its operations. One security chief even gave me a detailed briefing of how Wagner was using the territory of a country where it had a presence to recruit opponents of his regime and form them into an armed group that, once trained, could be sent back to try to overthrow the government or at least cause considerable mischief.

Since Prigozhin, Wagner group co-founder and military commander Dmitry V. Utkin, and logistics chief Valery Y. Chekalov were all aboard the jet that went down on August 23, the future of the enterprise they built remains to be determined. The simultaneous elimination of all three certainly facilitates what is said to be the Kremlin’s preferred scenario: the takeover of the group as a whole by the Russian authorities. The call on Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar in Benghazi just one day before by Russian deputy defense minister Yunus-Bek B. Yevkurov, himself a career airborne commando and military intelligence (GRU) officer, was reported to have been for purposes of assuring the Libyans of seamless continued support “under new management.” Another potential scenario, perhaps less likely in the absence of Prigozhin and his deputies, is the emergence of two Wagner successor groups, one directly controlled by the Russian Defense Ministry, possibly via the GRU, and another retaining autonomy. This may have been what Prigozhin was aiming at as he scurried across Africa during his last days. Finally, there is the possibility that the network fragments into multiple discrete units, each acting opportunistically where and when it can. While some Western policymakers and analysts evince a relish for this outcome, as with terrorist groups, the loss of central leadership among organizations can often lead to increased violence and destruction, not its diminution.

Beyond what organizational structure a post-Prigozhin Wagner Group might assume, there is the question of whether or not the successor or successors can maintain the complex web of not just mercenary forces and arms traffickers, but also various commercial enterprises and trade links that enabled its hitherto rapid expansion and, indeed, high profitability. Can any governmental bureaucracy, much less a Russian one, really be run in an entrepreneurial fashion? On the other hand, without the vast profits generated by the businesses—a report by The Sentry in June 2023 documents, for example, the acquisition of a single gold mine with a deposit valued at $2.8 billion—how sustainable are the military operations far from the war in Ukraine?

These questions aside, however, it is important to ask why Wagner has been and continues to be successful in Africa. The answer lies in understanding the demand for what Prigozhin offered regimes, both incumbent and potential. Two things stand out in particular:

Regime survival. Two days before his death, Prigozhin spoke up on camera for the first time since the June mutiny, appearing in a video originally posted to Telegram channels affiliated with Wagner. In his short address, the mercenary chief declared: “Wagner is conducting reconnaissance and search operations, making Russia even greater on every continent—and Africa even more free. Justice and happiness for the African nations.”

Notwithstanding his soaring rhetoric, Wagner’s value proposition to regimes in Africa is very basic: regime survival. With the exceptions of Libya and, much more recently, Sudan, Wagner’s hitherto modus operandi has been to target weak, embattled sovereigns like the CAR’s internationally-recognized government which, at the time the first Russian “civilian instructor” (as the deployed Wagner personnel were euphemistically described then) arrived in early 2018, was barely able to secure the capital of Bangui. Not only did Wagner paramilitaries provide protection for President Faustin-Archange Touadéra, but Russian operatives also soon became critical players in efforts to ensure that he “won” reelection in 2020. More recently, they deployed to arrange the August 5 referendum which supposedly resulted in 95 percent of votes approving constitutional changes that abolished presidential term limits and extended the mandate from five to seven years. No wonder Touadéra hosted Prigozhin in the presidential palace on the banks of the River Ubangi.

The importance of regime survival is not to be underestimated when one contrasts the experience of CAR’s Touadéra, who is looking forward to a prolonged tenure, with the fate of four victims of the rash of military coups in the Sahel since 2020—Presidents Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta of Mali, Roch-Marc Kaboré of Burkina Faso, and, most recently, Mohamed Bazoum of Niger—who, despite being staunch Western allies with especially close ties to France, were overthrown while French troops stationed in their countries did nothing. In the case of the recent coup in Niger, Le Monde has even confirmed an allegation by the putschists that the now-deposed Nigerien government asked it to intervene to rescue the president in the early hours of the coup, but French authorities did not authorize the operation. The coup this week in Gabon only underscores the total dénouement of what was once Françafrique: if a garrison of some 400 French troops cannot prevent the overthrow of a President Ali Bongo Ondimba who, like his late father before him, has been a staunch ally of France, why would any government want to risk incurring the wrath of anti-French populist sentiment by having them around?

And it is not just the historical baggage of Western allies or even the questionable reliability of some of them, but African regional organizations like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) have not helped their credibility with not only their failure to prevent or reverse coups but their penchant for ostentatiously making threats they have neither the material capacity nor the political will to carry out.

Elite profit. While its services do not come cheap—the Wall Street Journal investigative team reported that Prigozhin sent a jet last fall to collect a $200 million payment he had earlier demanded from Haftar—Wagner has also taken care to allow local elites in partnership with it access to its globe-spanning network to sell natural resources that would otherwise be difficult for them to market, whether oil from Libya, gold from Mali and Sudan, or diamonds from the CAR. Were it to gain access to Niger—despite overtures from Prigozhin, the junta that took power in the Sahelian country had not opened the door for the Russian mercenaries, a clear red line for the United States as I have previously pointed out—this category might well include uranium.

Having established a quasi-permanent base in the CAR through de facto state capture, Wagner has used the country as a launchpad for entry to neighboring countries, including Sudan (where its non-state partner is the RSF) and Cameroon (where it engages in various rackets and through which it moves contraband to CAR). Earlier this year, it was reported that U.S. officials shared information with their Chadian counterparts of Wagner plots to destabilize their country from its CAR base. Since then, Chadian officials have maintained vigilance on their frontiers as well as focused on exiled dissidents who might fall in with the mercenaries. Similarly, following its initial entry into Mali, Wagner has not only expanded its presence in the country but used it as a bridge to Burkina Faso and other countries in West Africa. All this has bolstered the interests of Russia as well as the profits of Prigozhin and others. Even without the Wagner boss, the Kremlin will want to see the network survive and continue to exploit opportunities as they arise in Africa.

To counter this ongoing challenge, the United States, Europe, and their African partners will not only have to be conscious of the threat, but to craft their response by understanding what makes this malign element, irrespective of whatever form it assumes in the future, attractive to begin with.

Ambassador J. Peter Pham, a Distinguished Fellow at the Atlantic Council and a Senior Advisor at the Krach Institute for Tech Diplomacy, is the former U.S. Special Envoy for the Sahel and Great Lakes Regions of Africa.

Image: Shutterstock.