Why The Federal Reserve Accepted 2 Percent Inflation As The Norm

The Fed’s message that rates will stay near zero for a long time—and that inflation will be allowed to exceed 2 percent to make up for past misses—is meant to increase inflation expectations.

The unanimous decision of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to shift from inflation targeting to average inflation targeting is another step away from its mandate to achieve long‐run price stability. Section 2A of the Federal Reserve Act does not say the Fed’s long‐run objective should be 2 percent inflation. It calls for maintaining the growth of money and credit to “promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long‐term interest rates.” The legal basis for price stability has not changed, but the Fed’s interpretation of that responsibility has drifted, so that “price stability” now means an increase in the price level (P) that averages 2 percent over time, with the proviso that the average inflation target (AIT) must be “flexible.”

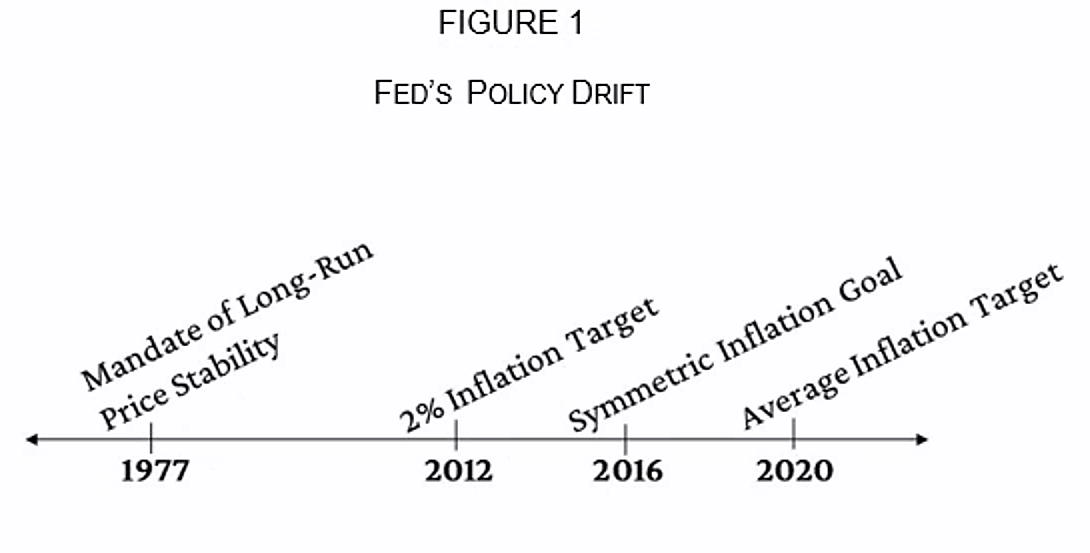

The Fed began to target inflation in 2012, when it moved to a 2 percent inflation target (IT), specified in the FOMC’s “Statement on Longer‐Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy” (also known as the “Consensus Statement”). In 2016, the Fed added flexibility to its IT by adopting a “symmetric inflation goal”; and, in 2020, the Fed amended its Consensus Statement and moved to a 2 percent average inflation target (AIT), announced by Fed Chairman Jerome Powell on August 27, at the Jackson Hole Conference. This policy drift is shown in Figure 1.

Price Stability Mandate

As former Fed governor Robert Heller notes: “The congressional mandate as stated in the Federal Reserve Act of 1977 is for the Fed to provide for ‘stable prices’—not 2 percent annual price increases.”

The term “stable prices” refers to a stable average level of money prices, not a stable rate of change of that level. It is problematic that so many people, Fed officials included, fail to make this distinction. The law of compound interest tells us that even a relatively low rate of inflation can have a considerable influence on the price level over time. For example, a 2 percent IT means that the average level of money prices doubles every 35 years thereby debasing the currency. If the time frame for an AIT of 2 percent is 35 years, then the price level will also double under the Fed’s new monetary framework.

Average Inflation Targeting

Despite the literal meaning of “stable prices,” the Fed has long equated fulfilling its mandate with achieving 2 percent inflation, while implicitly treating “maximum employment” as that employment level consistent with its 2 percent target. Yet it has not even succeeded in keeping the price level rising at a steady 2 percent trend. During the 1970s, inflation soared to double digits at the same time unemployment was rising; the result was stagflation. Paul Volcker brought inflation down and laid the basis for solid economic growth. Today, the Fed sees low inflation as a problem. The central bank has not been able to achieve its 2 percent IT since 2008, and its policy rate is at the zero lower bound (ZLB). Hence, since 1977, the trend of the price level has first drifted upwards and, since 2008, downwards.

The Fed has instituted AIT with the hope of keeping the trend of the price level stable—that is, “making up” for drift. Provided it is done with a reasonably short averaging “window,” AIT could indeed make the price level (P) more predictable than ordinary IT, precisely because it would eliminate P “drift” altogether (see Selgin). However, if the window is very long, or indefinitely so, and AIT is “asymmetric,” price level drift could instead end up becoming even more pronounced. As Selgin notes,

Faced with stiff‐enough opposition, the Fed might fail to carry out some or all of a needed correction [from overshooting its 2 percent AIT]. …Because the Fed’s efforts to make up for excessively low inflation are less likely to meet with similar opposition, the result could be an “asymmetrical” average inflation targeting strategy that allows the price level path to drift upwards. In that case, even if the Fed starts out with a clearly‐specified AIT rule, its reluctance to stick with it will cause the long‐run inflation rate to exceed the Fed’s target.

In his Jackson Hole speech, Chairman Powell made it clear that the central bank will follow a “flexible form” of AIT, leaving the “average” undefined. Consequently, a serious flaw with the new monetary framework is that, without a specific time frame, the term “average” is so open to abuse as to be almost meaningless. Without pinning down the time frame, it is impossible to say the AIT has been violated—merely, that the path of the price level is not on target.

Under the new framework, we can expect more than 2 percent inflation for some unspecified period to make up for shortfalls over another unspecified period, and vice versa. However, it will be difficult to return to 2 percent inflation once the Fed lets it drift above 2 percent. Congress is unlikely to tolerate the rise in unemployment and social unrest normally associated with disinflation in a world of sticky prices.

More importantly, average inflation targeting further expands the Fed’s discretionary authority. There is still no credible monetary rule to guide policy and anchor the long‐run price level. In this sense, Congress has failed in its duty to safeguard the purchasing power of the dollar—an important property right (Figure 2).

Note: Consumer price index for all urban consumers: all items in U.S. city average. Source: St. Louis Fed, FRED.

Rethinking the Fed’s Monetary Framework

In addition to price stability, the Fed has been tasked with achieving “maximum employment.” Just as the definition of “stable prices” is ambiguous—because it could reflect a stable rate of change in the price level or a stable price level—the term “maximum employment” has never been precisely defined.

Under the influence of the Phillips curve, policymakers assumed a tradeoff between unemployment and inflation: reducing unemployment was presumed to lead to higher inflation, at least in the short run. Since policymakers typically are myopic, they tried to exploit that tradeoff. However, under the new monetary framework, Chairman Powell and the FOMC have declared that the Phillips curve is flat and no longer a reliable policy guide. According to Powell, “a robust job market can be sustained without causing an outbreak of inflation.” Under the new framework, therefore, the Fed will not automatically increase its policy rate as the labor market heats up. In effect, greater weight is now being given to reducing unemployment and less to damping inflation expectations.

Logic Behind the New Framework

The logic behind the new framework is provided in Chairman Powell’s Jackson Hole speech. He explains that, while the public often considers low inflation preferable, persistently low inflation can lower long‐run inflation expectations. This becomes an issue when one considers that expectations directly influence the level of nominal interest rates. For a Fed that has consistently undershot its 2 percent long‐run inflation target, this is rightfully concerning. Without some force putting upward pressure on interest rates, the Fed will continue to operate with a reduced range of options, due to its proximity to the ZLB.

Questioning Conventional Wisdom

Claudio Borio, head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the Bank for International Settlements, has argued that erratic monetary policy can contribute significantly to financial booms and busts, impact resource allocation, and slow productivity growth. In his view, “the long‐term decline in real interest rates since at least the 1990s may well be, in part, a disequilibrium phenomenon, not consistent with lasting financial, macroeconomic, and monetary stability.” As he states:

The long‐term decline reflects, in part, asymmetrical monetary policy over successive financial and business cycles. Global disinflationary forces, in the wake of the globalization of the real economy and technological innovations, have kept a lid on inflation. Monetary policy has failed to lean against unsustainable financial booms. The booms and, in particular, subsequent busts have caused long‐term economic damage. Policy has responded very aggressively and, above all, persistently to the bust, sowing the seeds of the next problem. Over time, this has imparted a downward bias to interest rates and an upward one to debt, as indicated by the steady rise in total debt‐to‐GDP ratios.

For Borio, “[low] policy rates are not simply passively reflecting some deep exogenous forces; they are also helping to shape the economic environment policymakers take as given.” The Fed’s adherence to “lower for longer” is a case in point. The reach for yield (see Banerji; also Goldfarb and Minczeski) in an environment of near‐zero interest rates, engineered by the Fed and other central banks, can foster financial booms and slow productivity growth, thereby putting downward pressure on real rates.

Finally, Borio notes that “the well‐known limitations of expansionary monetary policy in tackling busts appear in a new light. It is not just that agents wish to deleverage and the transmission through banks is broken; easy monetary policy cannot undo the resource misallocations.” What needs to be done is to eliminate “the obstacles that hold back growth” by “facilitating balance sheet repair and implementing structural reforms.”

An important implication of Borio’s analysis, in the case of average inflation targeting, is the procyclical risk of a policy that raises inflation above its long‐run target only during expansions. If the result is more severe busts, the paradoxical end result could be that we get stuck at the ZLB more rather than less often (see Selgin).