The Zawahiri Era

Mini Teaser: Meet Ayman al-Zawahiri, the Egyptian doctor-turned-jihadist-mastermind—and the new head of al-Qaeda. He will out-terrorize his predecessor. Prepare for the new age of jihad.

ON MAY 2, 2011, al-Qaeda chief Osama bin Laden left this world for the next, and the American bipartisan political elite—not to mention the U.S.-Euro war-loving quintet made up of Senators John McCain, Joe Lieberman and Lindsey Graham, UK prime minister David Cameron and French president Nicolas Sarkozy—leapt off the precipice of simple unreality into the rarefied environs of true fantasy. They are behaving as if bin Laden’s death has ushered in an era in which the United States and the West will at long last get their way in the Muslim world through diktat backed by military force, which, of course, amounts to making our little Muslim brothers just like us . . . Au contraire.

ON MAY 2, 2011, al-Qaeda chief Osama bin Laden left this world for the next, and the American bipartisan political elite—not to mention the U.S.-Euro war-loving quintet made up of Senators John McCain, Joe Lieberman and Lindsey Graham, UK prime minister David Cameron and French president Nicolas Sarkozy—leapt off the precipice of simple unreality into the rarefied environs of true fantasy. They are behaving as if bin Laden’s death has ushered in an era in which the United States and the West will at long last get their way in the Muslim world through diktat backed by military force, which, of course, amounts to making our little Muslim brothers just like us . . . Au contraire.

Since 2001, ten thousand U.S. citizens have died, more than thirty thousand have been wounded or maimed, two U.S. field armies are quitting wars without winning, and the public purse will incur costs estimated at up to $4 trillion when all is said and done. Each component of this laundry list of failures is in one way or another attributable to bin Laden. No individual, moreover, has had a greater negative impact on Americans in the last fifty years. From the way U.S. citizens look at their government (can it protect us?), immigrants (what are they really up to in that garage?) or the police (how secure are our civil liberties?), the assumptions of everyday life have been changed for the worse by bin Laden’s words and deeds. At the least Americans will be able to welcome the absence of a man who for fifteen years bombed their cities, ships and embassies; killed their soldier-children; helped ruin their economy; and consistently made asses out of their presidents and generals. But while killing bin Laden is a significant achievement for the military and the CIA (and for the U.S. public), those levelheaded folks will take it for what it is, a major tactical victory that will only lead to a strategic defeat of the enemy should extreme—and highly unlikely—good fortune prevail.

Being a highly talented combination of seventh-century believer and twenty-first-century CEO, bin Laden built, in al-Qaeda, an absolutely unique Muslim organization: multiethnic, multilingual, organizationally sound and resilient, religiously tolerant and militarily effective. We will see in the next few years if bin Laden was the indispensable glue that kept al-Qaeda together or if his skill, his leadership and its nearly twenty-five years of being institutionalized as an organization created a survivable entity. The question on everyone’s lips is whether new al-Qaeda head Ayman al-Zawahiri is up to the job. My own bet is that al-Qaeda will survive, as it did after near economic ruin in Sudan (1994–96); after the pounding it took from the U.S.-NATO-Pakistan coalition (2001–02); and after the U.S. military helpfully killed Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, al-Qaeda’s chief in Iraq (2006), whose indiscriminate targeting of Muslims almost pushed al-Qaeda to the brink of defeat.

EVEN BEFORE 9/11, bin Laden made it clear to those taking time to read what he said—not many, sadly, in the last three U.S. administrations—that he knew the war he had declared on the United States in 1996 would last for decades and perhaps generations, and that he, naturally enough, would not live to see it through to the end. Indeed, he often said he wished to die fighting America; the U.S. Navy SEALs should expect a thank-you note from the great beyond. Wanting as protracted a war as possible—it was the only one Islamists could win, and the one Americans would surely lose—bin Laden set himself the goal of building an organization that could survive both a war against the U.S. superpower backed by its NATO vassals and his own capture or death. Concern about al-Qaeda’s survivability is such a strong and often-repeated theme in bin Laden’s oeuvre that the White House’s breathless post–May 2 “leaks” of data from his residence showing he worried about the group’s staying power say far less about bin Laden and al-Qaeda’s condition than they do about the failure of U.S. civilian and military officials to read and ponder their enemies’ words.

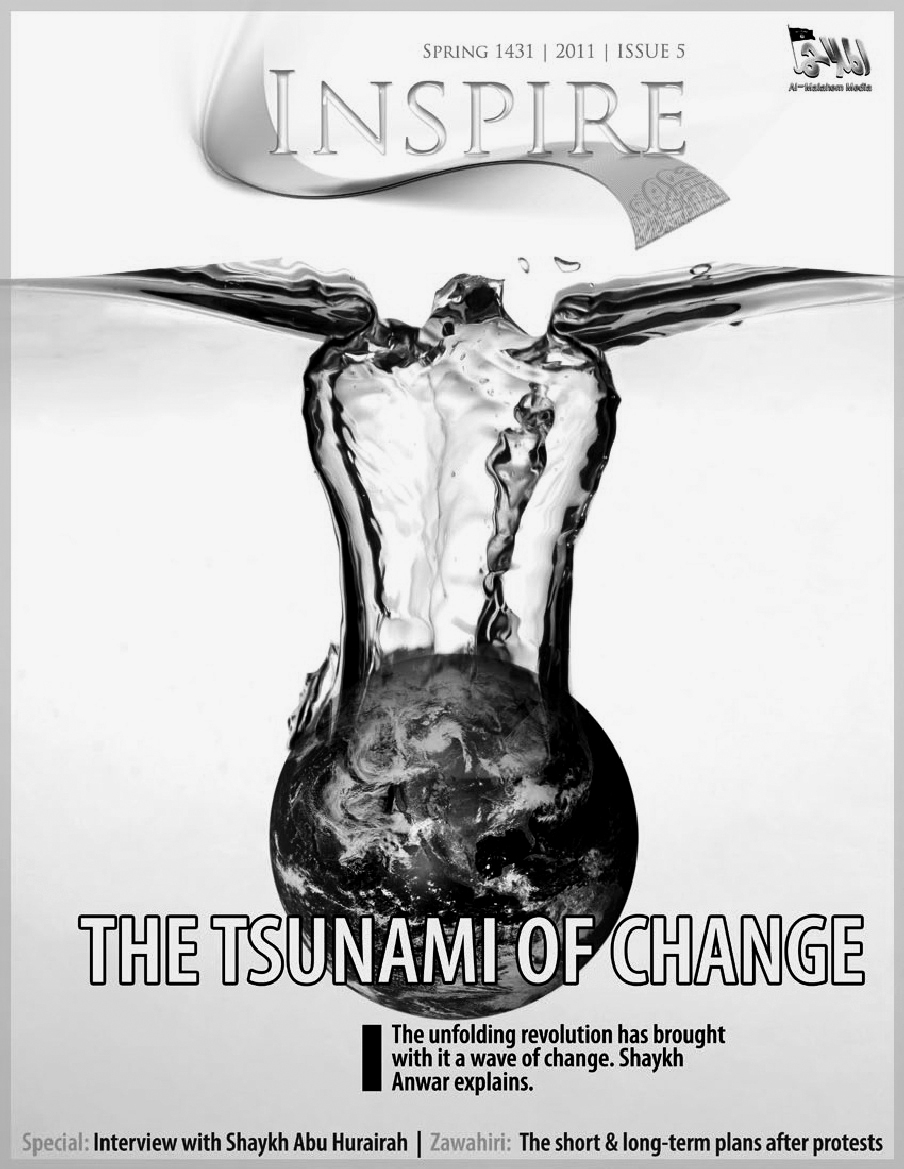

For all the Obama-administration rhetoric to the contrary, bin Laden’s creation of a survivable entity was an unqualified success. To protect his organization against decapitation—something he knew America’s legalistic “catch ’em, try ’em, hang ’em” ethos would focus on—bin Laden began dispersing al-Qaeda soon after 9/11. The first step was to send fighters home who were not needed in the early stages of war with the U.S.-NATO coalition; after all, the fewer fighters forced to run and hide in the Afghan mountains or Pakistan the better. The second step, so foolishly catalyzed by the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, was bin Laden and his senior lieutenants building and strengthening organizational offshoots in Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, the Levant, Palestine and North Africa. As he drew his last breath, in fact, bin Laden knew al-Qaeda’s horizontal growth since 2001 had given it seven locations from which to plan, train for and launch operations—as opposed to one at 9/11—none of which, save Pakistan, has been more than marginally damaged by U.S. or Western military forces over the last decade. He also knew that al-Qaeda’s multiyear investment in inciting young Muslims worldwide, from Nigeria to New Delhi to the North Caucasus, had been a substantial success. More specifically, al-Qaeda’s recruitment of talented, young U.S.-citizen Muslims—men such as the editor of the group’s online magazine Inspire, Samir Khan, senior operative and media adviser Azzam al-Amriki and public-preacher-cum-recruiter Anwar al-Awlaki—gave the organization’s media arm a powerfully influential means with which to promote war in the streets of the English-speaking world, especially in the United States, Britain, Canada, Australia, South Africa and India.

AYMAN AL-ZAWAHIRI, then, inherits an al-Qaeda organization that is larger, younger, better educated, much more geographically dispersed and has many more adherents than the one he joined in 1998. But as a figurehead, in several ways, he clearly lacks bin Laden’s exceptional (unique?) list of pertinent credentials. Though al-Zawahiri aided the Afghans as a physician during the anti-Soviet jihad, he acquired neither the combat experience nor the wounds from which bin Laden’s stature benefited. And he does not speak the same eloquent—even poetic—Arabic that Middle East scholar Bernard Lewis and others have appropriately ascribed to his predecessor. Moreover, while al-Zawahiri hails from a prestigious and fairly well-off Egyptian family, he does not have the durable Midas touch that bin Laden derived from his relatives’ enormous fortune and from the wealthy royal and nonroyal Gulf families he associated with and drew upon for funding. Finally, al-Zawahiri lacks the charisma for young Muslim males that bin Laden gained through his personal Robin Hood–like history, his eloquence, and his impeccable record of matching words and deeds. If bin Laden was the daring, visionary and inspirational older brother, al-Zawahiri is more the sober, methodical and prudent uncle.

The issue, then, comes down to leadership. The chattering classes run strongly to the opinion that al-Zawahiri will fail and preside over al-Qaeda’s decline-to-destruction because he is too abrasive, too dictatorial, too Egypt-centric, too vicious and bloodthirsty, too focused on the Arab world and too pedestrian to fill bin Laden’s shoes. There is a good deal of truth in this analysis, but most of the evidence supporting it was acquired before he joined al-Qaeda in 1998. A careful reading of al-Zawahiri’s enormous literary output since then—again, not a common activity in the West—shows bin Laden’s impact on him was profound. From being an Egypt-centric fighter, he became an anti-U.S. firebrand; from being obsessively clandestine, he became an ace media manipulator and propagandist; and from being a cold-blooded and fairly indiscriminate killer, he became more circumspect and careful, going so far as to reprimand Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in July 2005 for being as bloody-minded and inconsiderate of Muslim public opinion as he (al-Zawahiri) was before joining al-Qaeda. And his prudence is not necessarily weakness, especially when found in a person who is also pious, talented, personally brave, and—like bin Laden—not only ruthless but blessed with an uncanny knack for surviving against very long odds.

It would be reckless to assume al-Zawahiri has learned little and changed nothing since the mid-1990s. He does succeed bin Laden with potentially debilitating personality traits and leadership quirks, but he would have to ignore the advice and experience of his lieutenants as well as the guidance of al-Qaeda’s top decision-making body, the Shura Council, and then deploy and intensify his negative traits and idiosyncrasies with an eye toward deliberately destroying al-Qaeda and throwing away his own life’s work to undermine the promising opportunities he inherited from bin Laden. It may well be that al-Zawahiri will never be bin Laden, but there is also zero evidence that he is a reckless, supremely egotistical fool bent on self- and organizational immolation. “Any leadership flaw,” al-Zawahiri has written, “could lead to an historic catastrophe for the entire ummah,” and he has three able, organization-bred and combat-experienced lieutenants—Atiyah Abd al-Rahman, Abu Yahya al-Libi and Abu Basir Naser al-Wayhashi—who will keep him focused. (Al-Zawahiri’s deputy is likely to be one of the three, probably Atiyah, who was bin Laden’s operations chief.)

Image: Pullquote: The motivation for al-Qaeda to fight the United States is the same as when bin Laden declared war in 1996—Israel, oil, intervention, occupation and support for tyranny.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: The motivation for al-Qaeda to fight the United States is the same as when bin Laden declared war in 1996—Israel, oil, intervention, occupation and support for tyranny.Essay Types: Essay